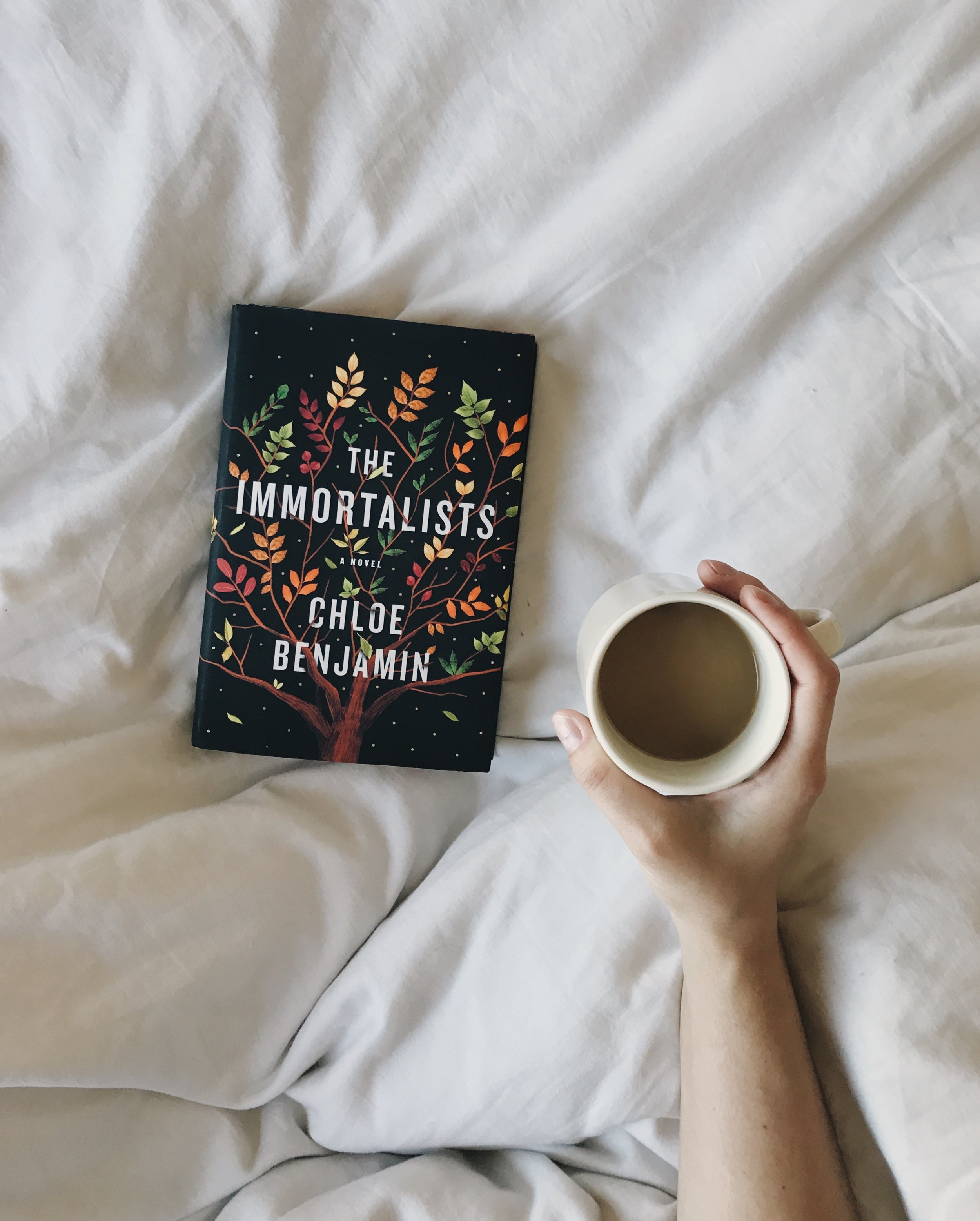

I just finished The Immortalists, and it was lovely. A book has at least three stars for me if it makes me think at the end. This book, written in third person, is split up into four different sections, one for each sibling: Simon, Klara, Daniel, and Varya.

As children in New York, they go together to see a traveling fortune teller who tells them the days they will each die. It's an incredibly impactful event for them as children and shapes the rest of their decisions in life.

It's a bit of a sad book and feels rushed at times, but I think it's a beautiful look at how we should live our lives, even though we all know we are going to die. It's also an enjoyable meditation on family—specifically with siblings—and how choices affect their relationships.

This book made me long for those relationships and appreciate the ones I do have. It's a reminder to take an extra beat to reflect on the small things in life—the smell of your sister's hair or the way your brother's arms feel when he pulls you in for a hug.

Read this book if you like a little bit of everything—mystery, crime, romance—in one package.

Don't read if you prefer not to feel a bit melancholy at the end of a book.

Four out of five stars.

Simon's section:

“They sit in companionable silence. Freestanding wood piers rise from the water like tree trunks. Every so often, a bird lands on one, screeches dictatorially, and departs with a thick flapping noise. Simon is watching this happen when Robert turns, dips his head, and kisses him on the mouth. Simon is stunned. He keeps very still, as if Robert might otherwise fly away like the gull.”

“Who is his Lord, his refuge? Simon doesn’t think he believes in God, but then again, he’s never thought God believed in him. According to the Book of Leviticus, he’s an abomination. What kind of God would create a person of which He so disapproved? Simon can only think of two explanations: either there’s no God at all, or Simon was a mistake, a fuck-up. He’s never been sure which option scares him more.”

“They spend two years like this. Simon makes the coffee; Robert makes the bed. Everything is new until it isn’t anymore: Robert’s frayed sweatpants, his groan of pleasure. How he trims his nails weekly—perfect, translucent half-moons in the sink. The feeling of possession, foreign and heady: My man. Mine. When Simon looks back, this period of time feels impossibly short. Moments come to him like film slides: Robert making guacamole at the counter. Robert stretching by the window. Robert going outside to snip rosemary or thyme from the clay pots in their garden. At night, the street lamps shine so brightly, the garden is visible in the dark.”

Klara's section:

“Most adults claim not to believe in magic, but Klara knows better. Why else would anyone play at performance—fall in love, have children, buy a house—in the face of all evidence there’s no such thing? The trick is not to convert them. The trick is to get them to admit it.”

Varya's Section:

“Varya has had enough therapy to know that she’s telling herself stories. She knows her faith—that rituals have power, that thoughts can change outcomes or ward off misfortune—is a magic trick: fiction, perhaps, but necessary for survival. And yet, and yet: Is it a story if you believe it? Her deeper secret, the reason she doesn’t think she’ll ever be rid of the disorder, is that on some days she doesn’t think it’s a disorder. On some days, she doesn’t think it’s absurd to believe that a thought can make something come true.”

“To look forward or back must have felt ungrateful, like testing fate—the free present a vision that might vanish if he took his eyes away from it. But Varya and her siblings had choices, and the luxury of self-examination. They wanted to measure time, to plot and control it. In their pursuit of the future, though, they only drew closer to the fortune teller’s prophecies.”

“Varya knows that stopping aging is as improbable as the idea that a compulsion can keep something bad from happening. But she still wants to shout: Don’t go.”